Modern geriatric principles do not view age-associated changes in humans as a pathological process; aging is considered a normal characteristic of the organism. The biological, physiological, and psychological processes of aging and their impact on human life are determined by the domains of individual vitality of the organism.

The following domains are identified:

Focusing on the somatic domain, its structure is closely linked to the development of chronic diseases. According to World Health Organization documents on non-communicable diseases, in the 21st century, 80% of deaths in developed countries will be associated with four groups of pathological conditions: cardiovascular diseases (arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease), oncological diseases, bronchopulmonary diseases (primarily chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and diabetes mellitus.

The onset of many diseases is preceded by the presence and realization of certain risk factors (modifiable and non-modifiable), which initiate a mechanism of pathophysiological changes in the organism, leading to adverse aging. Interrupting this chain of changes at the initial stages with pharmacological and non-pharmacological means can prevent or slow down the progression of diseases. Age, gender, or genetic predisposition are not modifiable, but they must be considered when assessing cardiovascular risk.

Let’s examine the main modifiable risk factors for cardiorespiratory diseases:

The first three factors are included in the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome (MS), which increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes fivefold and doubles the risk of cardiovascular diseases. MS also contributes to the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gallstone disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and in women, it is associated with the development of polycystic ovary syndrome, and in older patients, with cognitive impairments and dementia. The WHO characterizes MS as the “pandemic of the 21st century.”

Dyslipidemia is widespread among the population and is characterized by a low level of awareness of one’s cholesterol and lipid levels. The lipid profile in MS is marked by increased triglycerides, low and very low-density lipoproteins, and decreased high-density lipoproteins, leading to systemic endothelial dysfunction, which is the basis for the development of coronary atherosclerosis and its transition to coronary heart disease and arterial hypertension.

Hyperuricemia, with uric acid levels above 360 μmol/L, is an established risk factor for gout development, a predictor of increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and mortality. The pathogenesis involves similar processes of chronic inflammation of the vascular wall, leading to endothelial dysfunction. Hyperuricemia is closely linked to glucose tolerance impairment, the development of arterial hypertension, and osteoarthritis.

Obesity is a significant global health issue, with over 4 million people dying annually from overweight or obesity-related consequences. According to WHO projections, by 2030, 60% of the world’s population will suffer from obesity. In Russia, as of 2016, 62% of the population had excessive body weight, and 26.2% were obese. Obesity is seen as a precursor to low-grade chronic immune inflammation, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, certain cancers, osteoarthritis, and other diseases.

Hypokinesia affects more than a quarter of the world’s adult population, lacking sufficient physical activity. The negative impact of hypokinesia becomes more pronounced after the age of 30-40, coinciding with an increased risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Regular physical exercises have been shown to positively influence vascular tone, angiogenesis, and reduce the severity of ischemic events, thus preventing various diseases and mortality.

Smoking, according to WHO data, was prevalent among 22.3% of the global population in 2020. Smoking more than doubles the likelihood of developing coronary heart disease and increases the risk of lung cancer by 90%. The recent rise in the use of electronic cigarettes and vaping devices, perceived as a safer alternative to smoking, has led to numerous cases of lung injury associated with vaping (EVALI) and several fatalities. The main damaging agent is believed to be vitamin E acetate, which, when heated, has a destructive effect on the bronchopulmonary system and alveolar surfactant.

Quitting smoking improves lung and cardiovascular function, increases physical performance, and reduces chronic disease-related work absences. However, quitting smoking can be a stressor for a habitual smoker. A comprehensive approach, including establishing strong motivation, setting a clear timeline for quitting, and possibly using pharmacological support, can help achieve success in overcoming this harmful habit.

The combination of several risk factors significantly increases the likelihood of developing diseases, and an established diagnosis carries the risk of developing other pathologies. The coexistence of two or more chronic diseases, either etiopathogenetically related or coincidental in onset, regardless of the activity of each, is termed “comorbidity.” Its prevalence reaches 62% among individuals aged 65-75 and 82% among those older than 85. Comorbidity is an independent risk factor for mortality and severely worsens the prognosis for the patient, also complicating therapy due to the necessity for polypharmacy.

Maintaining somatic health is crucially dependent on normalizing lifestyle: abstaining from alcohol (as there is no safe level of alcohol consumption according to WHO) and other harmful habits, balancing work and rest, adequately managing stress triggers, and ensuring a full 7-8 hours of sleep. Proper sleep hygiene, including consistent sleep and wake times, avoiding caffeine and tea in the evening, taking short walks before bedtime, ventilating the room, taking warm baths, sound and light insulation, and minimizing gadget use before sleep, contributes to sleep normalization.

The development of acute inflammation is essential for the formation of the body’s protective response to invading pathogens or acute traumatic injuries. This process facilitates cell recovery and renewal in many tissues. In contrast, chronic low-grade immune inflammation, not associated with the presence of an infectious agent but arising from hemodynamic overloads, ischemia, intoxications, etc., represents a significant risk factor for morbidity and mortality among the elderly. Aging is associated with immune dysregulation: an increase in pro-inflammatory markers in the blood (in the absence of obvious triggers) while simultaneously decreasing the ability to resolve inflammatory responses to common immunogenic stimuli. In older adults with chronic non-communicable diseases, an increase in the following inflammation markers is observed: interleukin-1, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, interleukin-13, interleukin-18, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, C-reactive protein, interferons alpha and beta, transforming growth factor-beta, and serum amyloid A. There is compelling evidence that elevated circulating inflammation mediators and the presence of age-associated diseases (coronary heart disease, arterial hypertension, gout, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, malignant neoplasms, anemia) contribute to the progression of chronic low-grade immune inflammation.

The process of aging in terms of inflammatory reactions activation can be divided into two types:

In elderly and senescent individuals, there are all the macroscopic and functional prerequisites for the activation of the immune response in an unfavorable manner: decreased elasticity, rigidity, and atherosclerosis of the aorta and major arteries; hypoxic damage and age-related functional restructuring of diencephalic-hypothalamic structures of the brain; deterioration of hemorheology, microcirculation, and oxygen exchange in tissues; a tendency towards vasospastic reactions due to increased sodium, calcium, and water content in the vascular wall, as well as under the influence of emotions, pain sensations; ischemic changes in the heart and kidneys; age-related changes in the sympathetic-adrenal and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems; the presence of obesity, decreased physical activity, the duration of harmful habits (smoking, alcohol).

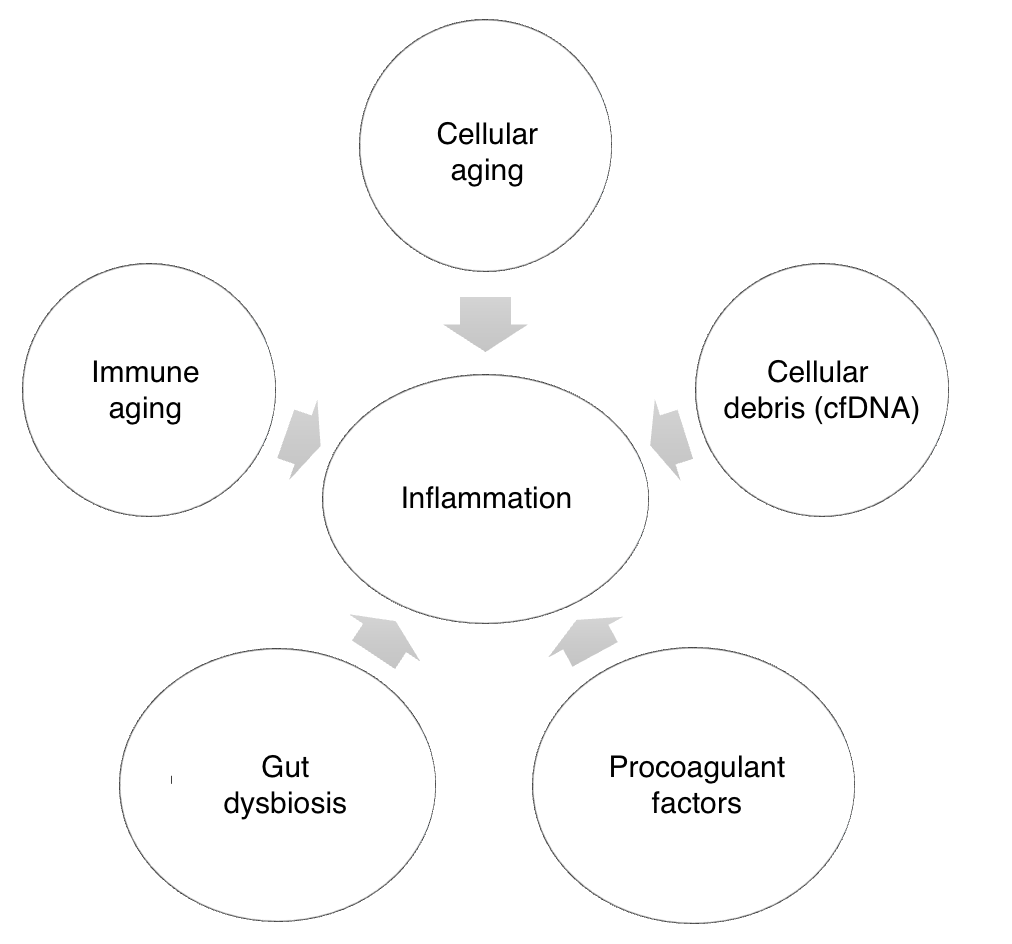

Microscopic prerequisites for chronic immune inflammation include cellular aging processes (cell senescence), procoagulant factors, cellular debris such as circulating mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), gut dysbiosis, and immune aging (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Key microscopic factors of chronic inflammation

With age, the system for eliminating cellular debris fails to function adequately, leading to the accumulation of protein molecules (immunoglobulins, mtDNA) and activation of the innate immune system in the form of persistent inflammation. Circulating mitochondrial DNA, due to its bacterial origin, enhances the inflammatory response by interacting with receptors similar to those involved in pathogen reactions.

The barrier function of the mucosal lining of the oral cavity and intestine against infectious agents also deteriorates with age. The gut microbiota of elderly people shows a decrease in anti-inflammatory flora (Clostridium cluster XIVa, Bifidobacterium spp., F. prausnitzii) and an increase in inflammatory and pathogenic flora (including Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Enterobacter spp.).

Cellular aging is an irreversible halt in the cell cycle, enacted through various endogenous mechanisms (DNA damage, telomere dysfunction, oxidative stress, epigenetic alterations, mitogenic signaling). With age, cell senescence increases, along with the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines, sustaining low-grade inflammation. Experiments on laboratory animals indicate that removing aging cells weakens the progression of age-related disorders, which could potentially be used to combat age-associated diseases and extend lifespan.

Immunosenescence is the dysregulation of the innate immune system: increased susceptibility to malignant and autoimmune diseases, infections, decreased immune response to vaccination, and impaired wound healing. The mechanisms underlying immune dysregulation remain not fully understood but are presumably related to changes in the number and functions of innate immune cells.

The coagulation and fibrinolysis system. Due to physiological aging processes, concentrations of fibrinogen, blood coagulation factors V, VII, VIII, and IX in plasma increase, which may explain the higher cardiovascular risk observed in older adults. Furthermore, according to existing studies, the activation of the coagulation cascade initiates the aging process and inflammatory cell changes through insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5), involved in fibrotic and inflammatory gene transcription.

Peptides (from Greek πεπτός — nutritious) are chemical compounds whose molecules are constructed from residues of α-amino acids linked in a chain by peptide (amide C(O)NH) bonds.

Peptides are present in all living organisms and act as signaling molecules involved in maintaining the constancy of their internal environment. Due to their diverse bioregulatory effects on the body, peptides are widely used in various medical fields: from stimulating tissue regeneration to regulating the immune function of the body in combating bacterial and viral infections, and they are used as biomarkers for the detection of ischemic stroke or lung cancer, in vaccination. One of the most well-known peptide drugs is insulin. Many other compounds with hormonal activity (such as glucagon, oxytocin, vasopressin), compounds regulating gastrointestinal tract processes (gastrin, gastric inhibitory peptide, hepatoprotective peptides), substances with analgesic effects (opioid peptides), organic substances regulating higher nervous activity, blood pressure, and vascular tone (angiotensin II, bradykinin, and others), antimicrobial peptides, and immunomodulatory peptides (Palmitoyl Tetrapeptide-3, thymogen, thymalin, Thymulen TM) also have a peptide nature.

Peptides are divided into natural and synthetic based on their production method. Natural peptides are derived from plant or animal raw materials, while synthetic peptides are “assembled” from amino acid residues in a specific sequence.

Thus, the study of the impact of peptides on the functions of the neuroimmune endocrine system is a promising and rapidly developing area of medicine, due to their high biological activity and specificity of action. The possibilities of synthesizing peptide products to enhance the regenerative capabilities of vascular endothelial cells and reduce the severity of chronic systemic inflammation are actively being explored. The study of their impact on stem cells to slow down the aging processes of the body is also of interest.

The modern understanding of favorable aging encompasses psychological, physical, and social health, functioning, life satisfaction, a sense of purpose, financial stability, learning new things, achievements, appearance, activities, sense of humor, and spirituality.

To assess the state of the somatic domain, preventive and screening programs aimed at preventing premature aging of the population and early detection of patients with risk factors (RFs) for age-associated diseases are necessary.

To determine the type of obesity, three indicators are assessed: Waist Circumference (WC), Hip Circumference (HC), and the Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR).

Table 1 – Criteria for Diagnosing Metabolic Syndrome.

| Primary | |

| Abdominal obesity: | Waist circumference >80 cm in women and >94 cm in men |

| Additional | |

| Hypertension: Blood pressure | >140/90 mm Hg |

| Elevated triglycerides: | >1.7 mmol/L |

| Reduced HDL cholesterol: | <1.0 mmol/L in men, <1.2 mmol/L in women |

| Elevated LDL cholesterol: | >3.0 mmol/L |

| Hyperuricemia: Fasting plasma glucose | >6.1 mmol/L |

| Impaired glucose tolerance: | Plasma glucose 2 hours after glucose tolerance test within 7.8-11.1 mmol/L |

| Hyperuricemia: | >360 µmol/L in women, >420 µmol/L in men |

This method allows for the assessment of an individual’s risk of dying from cardiovascular diseases within the next 10 years. It is recommended for countries with a very high level of cardiovascular disease mortality (including Russia). The overall risk assessment using SCORE-2 is conducted in asymptomatic adults over the age of 40, without cardiovascular diseases (CVD), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or familial hypercholesterolemia (FH).

The cardiovascular risk assessment in these algorithms takes into account age, gender, smoking status, systolic blood pressure level, and non-HDL cholesterol level.

Table 2 – Scale for Global Assessment of 10-Year Cardiovascular Risk

| Risk Level | Criteria |

| Extreme | The combination of clinically significant cardiovascular disease caused by atherosclerosis, with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) / or Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH), or two cardiovascular events (complications) within 2 years in a patient with cardiovascular disease caused by atherosclerosis, despite optimal lipid-lowering therapy and/or achieved LDL cholesterol level ≤1.5 mmol/L. |

| Very High | – Documented atherosclerotic CVD, clinically or through diagnostic results, including past acute coronary syndrome (ACS), stable angina, heart valve surgery, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or other arterial surgeries, stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), peripheral artery disease; – Atherosclerotic CVD based on diagnostic data – significant carotid artery stenosis (stenosis >50%); – Diabetes Mellitus with target organ damage, ≥3 risk factors, early onset of Type 1 Diabetes with a duration of >20 years; – Severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <30 ml/min/1.73 m²; – SCORE-2 for individuals aged <50 years ≥7.5%, for individuals aged 50-69 years ≥10%, and SCORE-2-OP for individuals aged ≥70 years ≥15%; – Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) combined with atherosclerotic CVD or with risk factors. |

| High | – Total Cholesterol (TC) >8 mmol/L and/or LDL Cholesterol (LDL-C) >4.9 mmol/L and/or Blood Pressure (BP) ≥180/110 mm Hg; – Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) without risk factors; – Diabetes Mellitus (DM) without target organ damage, DM duration ≥10 years, or with risk factors; – Moderate Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) with Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) 30-59 ml/min/1.73 m²; – SCORE-2 for individuals aged <50 years ≥2.5 – <7.5%, for individuals aged 50-69 years ≥5 – <10%, and SCORE-2-OP for individuals aged ≥70 years ≥7.5% and <15%; – Hemodynamically insignificant atherosclerosis of non-coronary arteries (stenosis(-es) >25-49%). |

| Moderate | – Young patients (Type 1 Diabetes under 35 years, Type 2 Diabetes under 50 years) with a diabetes duration of <10 years without target organ damage and risk factors; – SCORE-2 for individuals under 50 years <2.5%, for individuals aged 50-69 years <5%, and SCORE-2-OP for individuals aged ≥ 70 years <7.5%. |

| Low | – SCORE-2 for individuals aged 40-69 years and SCORE-2-OP for individuals aged ≥ 70 years <1%. |

The SHSQ-25 questionnaire for assessing suboptimal health status is designed for screening diagnosis of a patient’s health status. To respond to each question, the patient selects one of five options: 1) never or almost never (0 points); 2) occasionally (1 point); 3) often (2 points); 4) very often (3 points); 5) always (4 points). A score is assigned based on the total points of the entire questionnaire, and for 5 separate scales: “immunity” (questions 1, 17, 25), “cardiovascular system” (questions 11-13), “digestion” (questions 14-16), “mental status” (questions 18-24), and “fatigue” (questions 1-6). A total suboptimal health status score of more than 14 requires more in-depth examination across all five scales.

Table 3 – Questionnaire for Assessing Suboptimal Human Health Status

| No. | How often does this happen to you? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | Do you experience fatigue not related to increased physical activity? | |||||

| 2 | Do you experience fatigue that persists after rest? | |||||

| 3 | Do you experience sleepiness during work? | |||||

| 4 | Are you bothered by headaches? | |||||

| 5 | Do you experience dizziness? | |||||

| 6 | Do you feel pain or fatigue in your eyes? | |||||

| 7 | Do you have a sore throat? | |||||

| 8 | Are you bothered by stiffness, discomfort in muscles or joints? | |||||

| 9 | Are you bothered by pain in your neck, shoulders, lower back? | |||||

| 10 | Do you feel heaviness in your legs while walking? | |||||

| 11 | Do you experience shortness of breath at rest? | |||||

| 12 | Do you feel tightness in your chest? | |||||

| 13 | Do you experience rapid heartbeat? | |||||

| 14 | Do you have a decreased appetite? | |||||

| 15 | Are you bothered by heartburn? |

The humoral adaptive immune response is based on the production of antibodies (Ab). To assess this component, studies are conducted to characterize the functional activity of the B-cell component, including the determination of immunoglobulin (Ig) concentrations, levels of specific antibodies, and circulating immune complexes (CIC). The cellular type of response is characterized by the production of antigen-specific B and T lymphocytes.

Diagnosis of “Immune” Micronutrient Deficiencies

Table 4 – Assessment of Vitamin D Levels in Blood Serum

| Classification | Vitamin D Levels in Blood (25(OH)D) | Clinical Manifestations | Therapy Regimen (Under Blood Test Monitoring) |

| Severe Vitamin D Deficiency | <10 ng/ml (<25 nmol/l) | High risk of rickets, osteomalacia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, myopathy, falls, and fractures | – 50,000 IU weekly for 8 weeks orally <br> – 200,000 IU monthly for 2 months orally <br> – 150,000 IU monthly for 3 months orally <br> – 6,000 – 8,000 IU daily |

| Vitamin D Deficiency | <20 ng/ml (<50 nmol/l) | Risk of bone loss, secondary hyperparathyroidism, falls, and fractures | – 50,000 IU weekly for 4 weeks orally <br> – 200,000 IU once orally <br> – 150,000 IU once orally <br> – 6,000 – 8,000 IU daily for 4 weeks orally |

| Vitamin D Insufficiency | 20-30 ng/ml (50-75 nmol/l) | Low risk of bone loss and secondary hyperparathyroidism, neutral effect on falls and fractures | – 50,000 IU weekly for 4 weeks orally <br> – 200,000 IU once orally <br> – 150,000 IU once orally <br> – 6,000 – 8,000 IU daily for 4 weeks orally |

| Adequate Vitamin D Levels | >30 ng/ml (>75 nmol/l) | Optimal suppression of parathyroid hormone and bone loss, 20% reduction in falls and fractures | – 1,000 – 2,000 IU daily orally <br> – 6,000 – 14,000 IU once weekly orally |

| Levels with Potential Toxicity | >150 ng/ml (>375 nmol/l) | Hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, calciphylaxis | Discontinue Vitamin D. |

Table 5 – Assessment of Zinc Levels in Blood Serum

| Classification | Zinc Level, µmol/L |

| Deficiency | Women: <10.7; Men: <11.1 |

| Normal Range | Women: 10.7-17.5; Men: 11.1-19.5 |

| Daily Requirement | 11 mg/day |

| Pregnancy & Lactation Requirement | 12-15 mg/day |

| Toxicity Threshold | Toxicity Threshold |

Table 6 – Assessment of Vitamin C Levels in Blood Serum

| Classification | Vitamin C Level, µg/ml |

| Deficiency | <4.0 |

| Normal Range | 4.0-15.0 |

| Excess | >15.0 |

There is no consensus on the exact daily requirement for Vitamin C; the recommended amount varies from 40 to 90 mg per day. Factors such as smoking, hemodialysis, and stress can increase the body’s need for Vitamin C. Consuming more than 2 grams of Vitamin C in a single dose may lead to stomach pain, diarrhea, and nausea, while 3 grams can elevate AST and ALT levels. Excess Vitamin C is excreted in urine and feces, potentially increasing oxalate levels in the urine, which, in the case of kidney pathology, can promote the formation of stones in the urinary tract.

This is used to study the impact of sleep on daily life, in conjunction with other criteria. The questionnaire is highly sensitive for identifying sleep disorders such as insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and narcolepsy. It includes a series of questions to assess the likelihood that a patient might doze off or fall asleep in the situations described below, compared to just feeling tired. The assessment of sleepiness is subjective and depends on its intensity, where 0 – would never doze/fall asleep; 1 – slight chance of dozing or falling asleep; 2 – moderate chance of dozing or falling asleep; 3 – high chance of dozing or falling asleep.

Table 7 – Epworth Sleepiness Scale

| Situation | Scale of Intensity |

| When sitting and reading | 0 1 2 3 |

| When watching television | 0 1 2 3 |

| When sitting inactive in a public place (e.g., in a theater, at a meeting) | 0 1 2 3 |

| When a passenger in a car for an hour without a break | 0 1 2 3 |

| When lying down to rest during the day, if circumstances permit | 0 1 2 3 |

| When sitting and talking to someone | 0 1 2 3 |

| When sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol | 0 1 2 3 |

| In a car, while stopped for a few minutes | 0 1 2 3 |

The Mediterranean diet is a system of healthy eating based on the principles of the traditional cuisines of Greece, Italy, Spain, and other countries bathed by the Mediterranean Sea. It primarily consists of plant-based foods: vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, legumes, seeds, herbs, and spices, with olive oil as the main source of healthy fats. Moderate consumption of fish, seafood, dairy products, and poultry is allowed, with very rare intake of red meat and sweets.Numerous studies have confirmed that the Mediterranean-type diet reduces the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, obesity, arterial hypertension, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; inflammatory bowel diseases; Type 2 diabetes; certain types of cancer, including hepatocellular and estrogen-independent cancers; dementia, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis; chronic fatigue, and poor mood in the elderly.

The diet is implemented alongside lifestyle normalization, abstaining from harmful habits, and maintaining proper physical activity levels.

Table 8: 7-Day Mediterranean Diet Menu with Minimum Recommended Caloric Intake

Monday

| Meal Time | Dish | Calories | Proteins (g) | Fats (g) |

Carbohydrates (g)

|

| Breakfast | Oatmeal (50g) with milk, berries (150g), almonds (25g), and Greek yogurt (2 tbsp) | 347 | 15 | 15 | 42 |

| Snack | |||||

| Lunch | Whole grain sandwich with turkey patty (200g), hummus, and tomatoes | 286 | 8 | 16 | 19 |

| Snack | |||||

| Dinner | Greek salad (250g) with feta cheese, whole grain bread (50g) | 223 | 5 | 6 | 10 |

Tuesday

| Meal Time | Dish | Calories | Proteins (g) | Fats (g) | Carbohydrates (g) |

| Breakfast | Omelet (3 eggs and 60ml 2.5% milk) with spinach (180g), basil, and tomato (100g) | 294 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| Snack | |||||

| Lunch | Steamed fish fillet (300g) and vegetable spaghetti (100g) with garlic oil | 432 | 34 | 22 | 24 |

| Snack | |||||

| Dinner | Vegetable soup with chicken broth (300g) | 156 | 12 | 7 | 10 |

Wednesday

| Meal Time | Dish | Calories | Proteins (g) | Fats (g) | Carbohydrates (g) |

| Breakfast | Cheese and tomato toast (200g) | 260 | 16 | 17 | 36 |

| Snack | |||||

| Lunch | Baked trout (100g), pasta with mozzarella (100g) | 510 | 36 | 10 | 71 |

| Snack | |||||

| Dinner | Lentil puree soup in vegetable broth (300g) | 240 | 11 | 34 | 5 |

Thursday

| Meal Time | Dish | Calories | Proteins (g) | Fats (g) | Carbohydrates (g) |

| Breakfast | Pancakes from skimmed cottage cheese (200g) | 272 | 32 | 5 | 24 |

| Snack | |||||

| Lunch | Pasta with shrimp (200g), seaweed salad (100g) | 558 | 28 | 32 | 34 |

| Snack | |||||

| Dinner | Steamed sea fish (200g), tomatoes (100g) | 244 | 34 | 10 | 2 |

Friday

| Meal Time | Dish | Calories | Proteins (g) | Fats (g) | Carbohydrates (g) |

| Breakfast | Oatmeal with yogurt (100g), toast with tomatoes and cheese (50g) | 240 | 17g | 16g | 30g |

| Snack | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lunch | Baked salmon (150g) with lima beans (100g) and sauce (Greek yogurt, lemon, olive oil) | 340 | 40g | 8g | 25g |

| Snack | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dinner | Fish patties (100g), boiled buckwheat (100g) | 210 | 20g | 36g | 28 |

Saturday

| Meal Time | Dish | Calories | Proteins (g) | Fats (g) | Carbohydrates (g) |

| Breakfast | Flakes with yogurt (200g), whole grain bread with hard cheese (50g) | 211 | 10g | 14g | 34g |

| Snack | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lunch | Vegetable stew (200g) with steamed sea fish (100g) | 306 | 39g | 13g | 7g |

| Snack | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dinner | Lentil puree soup in vegetable broth (300g) | 240 | 11g | 34g | 5g |

Sunday

| Meal Time | Dish | Calories | Proteins (g) | Fats (g) | Carbohydrates (g) |

| Breakfast | Couscous with milk (150g) with fruit pieces (100g) | 262 | 9 | 15 | 42 |

| Snack | |||||

| Lunch | Boiled seafood (200g), salad with greens, tomatoes, and olive oil dressing (150g) | 372 | 36 | 18 | 5 |

| Snack | |||||

| Dinner | Baked vegetables (eggplants, zucchinis, tomatoes, peppers, 200g) with bean puree (100g) | 275 | 17 | 29 | 9 |

Note: Due to the lack of specific menu details provided, Table 8 cannot be accurately created. If you have specific menu items or dietary guidelines for each day, please provide them for a detailed table.

For snacks, the following can be used: a handful of nuts (50g/day); fruits and vegetables (up to 300g/day); berries or grapes (up to 300g/day); Greek yogurt (100g/day), low-fat dairy products (150-200ml/day); dark chocolate (10g/day). One snack should account for 10% of the daily caloric intake. Fluid intake should average 30-50 ml/kg of body weight. The WHO-recommended salt limit is 5g per day (or 2g of sodium). According to the WHO, there is no safe level of alcohol consumption. Within the framework of the Mediterranean diet, the occasional consumption of dry red wine is allowed, not exceeding 200ml per day.

The appropriate amount of time to dedicate to moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity is at least 150-300 minutes per week; for high-intensity activities, at least 75-150 minutes per week is recommended. Alternatively, an equivalent mix of moderate and high-intensity physical activities throughout the week can offer additional health benefits.

The desired training effect on cardiovascular system function and metabolic rate is achieved at a heart rate (HR) level of 70-85% of the maximum permissible values, calculated using the formula: maximum allowable HR = 220 – age.

Older adults are advised to engage three times a week or more in diverse multi-component physical activities, emphasizing functional balance improvement and moderate to high-intensity strength training to enhance functional abilities and prevent falls.

Time should be organized to replace sitting or lying down with physically active tasks of any intensity (including low intensity). It’s essential to ensure that the physical exertion is realistic and corresponds to an individual’s actual capabilities.

Health status assessment, diagnostic testing, interpretation of results, and determination of indications for pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments in the outpatient care stage are initially conducted by a primary care physician (general practitioner or internist). It’s recommended to consult with a general practitioner or a gynecologist (for women) at least once or twice a year, and with specialized professionals as indicated. Annual health check-ups and sanatorium-resort treatments are advised as necessary.

“VIRUIN® PROimmunity” is a specially formulated dietary supplement aimed at bolstering natural immune defense mechanisms and mitigating chronic immune inflammation.

Inflammation is a fundamental bodily process that facilitates cell recovery and renewal but also underlies many chronic diseases. Addressing acquired and potential risk factors, combined with pharmacological support, helps reduce the severity of chronic immune inflammation, thereby enhancing patients’ quality of life and longevity.